As the race to implement fifth generation wireless (5G) intensifies, we should take a brief pause to address common misperceptions that could create major cybersecurity challenges among trading partners as well as from a national defense standpoint.

Let’s start with the term “5G,” which suggests that this technological advancement is iterative: We used to have 3G connectivity, which was replaced by 4G — now we’re getting 5G so everything will be a little faster. That’s not the case, as Inc.’s 5G primer asserts: “5G has been called the catalyst for the world’s fourth industrial revolution, and planning for that future is essential.”

Yes, 5G much, much faster (as measured by throughput) than 4G. More important, however, 5G offers dramatic reductions in latency (the time for data uploaded from one device to reach its target), dramatic increases in the number of devices and sensors that can connect to the network, and related mobility benefits in certain configurations. To put it less technically: moving from 4G to 5G is more like moving from landlines to cell phones, or even from no Internet to Internet.

A Brookings Institution report identifies and addresses what the co-authors view as a riskier 5G misperception: “For political purposes, that [5G] race has been defined as which nation gets 5G built first,” write former Federal Communications Chair Tom Wheeler and retired U.S. Navy Rear Admiral David Simpson. “It is the wrong measurement.” A better measure, Wheeler and Simpson assert, is the race to retool how the U.S. secures “the most important network of the 21st Century and the ecosystem of devices and applications that sprout from that network.” (Fresh research from Shared Assessments’ and The Ponemon Institute underscores the acute need for improvements in how companies and their vendors manage risks in the rapidly expanding ecosystem of connected devices and applications.)

Wheeler and Simpson acknowledge the tremendous benefits that 5G can deliver throughout most industries and the public sector while emphasizing that building 5G “on top of a weak cybersecurity foundation is to build on sand. This is not just a matter of the safety of network users, it is a matter of national security.” The co-authors stress that China poses a threat to 5G networks even when Huawei equipment is not part of U.S. 5G networks — and that all U.S. adversaries engaging in cyber warfare tend to target weak points in the commercial sector that provide critical infrastructure and/or products and services to critical infrastructure industries and companies.

Wheeler and Simpson highlight ways that 5G networks expand cybersecurity risks before proposing a sweeping, two-pronged risk-management strategy. They argue that 5G network security must address several structural vulnerabilities, including:

- Fewer hardware “choke points:” Previous wireless networks were based on hub-and-spoke designs that offered more control from a cybersecurity perspective; 5G networks are much more software based, which exposes them to the same cyberthreats targeting existing business. The software managing 5G networks can itself be vulnerable to attack, according to the co-authors.

- A larger attack surface: Much more bandwidth means more avenues of attack, Wheeler and Simpson point out, noting that “low-cost, short range, small-cell antennas deployed throughout urban areas become new hard targets.”

- Related Internet of Things (IoT) risks: Some of the most promising benefits of 5G relate to how the technology works with other advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI), edge computing and IoT. “Plans are underway for a diverse and seemingly inexhaustible list of IoT-enabled activities, ranging from public safety things, to battlefield things, to medical things, to transportation things—all of which are both wonderful and uniquely vulnerable,” Wheeler and Simpson note. For these innovations to succeed over the long haul, IoT risks need to be managed more effectively than they are today.

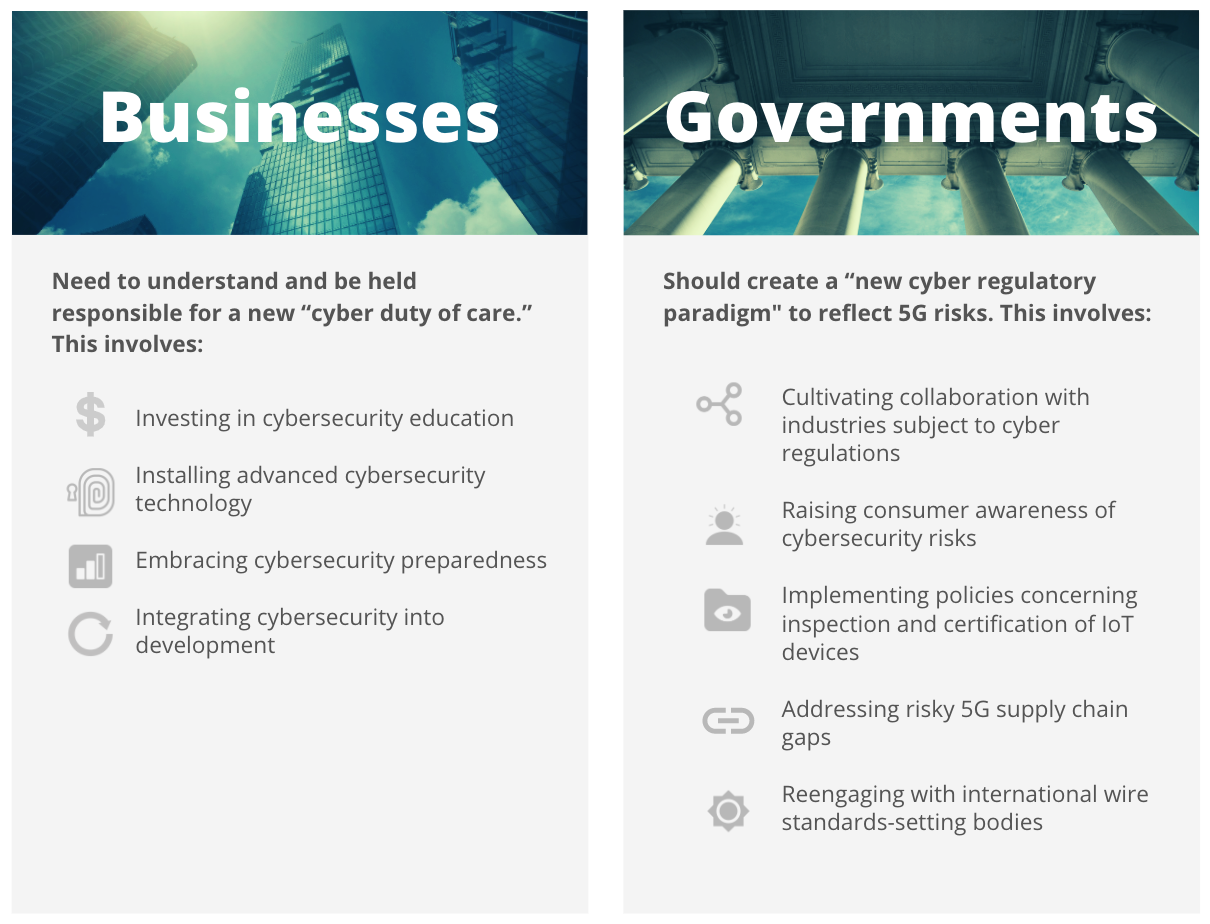

So, what’s the solution? Wheeler and Simpson propose two comprehensive steps — one geared toward industry and the other to government:

- Businesses need to understand and be held responsible for a new “cyber duty of care:” This involves investing far more in cybersecurity education, installing more advanced cybersecurity technology, embracing leading indicators of cybersecurity preparedness, and integrating cybersecurity deeper into application development cycles among other practices.

- Governments should create a “new cyber regulatory paradigm to reflect 5G risks: This involves cultivating more collaborative relationships with industries and businesses subject to cyber regulations, raising consumer awareness of cybersecurity risks, implementing policies concerning the inspection and certification of IoT devices, addressing risky 5G supply chain gaps, and reengaging with international wire standards-setting bodies such as the 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP).

These are big asks, to be sure, yet major progress is needed. Some progress already appears underway. In April, the Trump Administration published a seven-page document outlining a “National Strategy to Secure 5G of the United States” in tandem with the signing of the Secure 5G and Beyond Act into law. That law requires a policy to be identified along with an implementation plan, which is to be implemented within six months (by early October).